Opinion by Elise Tirza Ohene-Kyei MD, MPH, Chief Medical Officer, Poka Technology Ltd, creators of Poka Health App

“Beauty is pain.”

This is a saying we have all heard before and have even become accustomed to. But is it something we have to accept? Does beauty have to be pain, even at the cost of our lives?

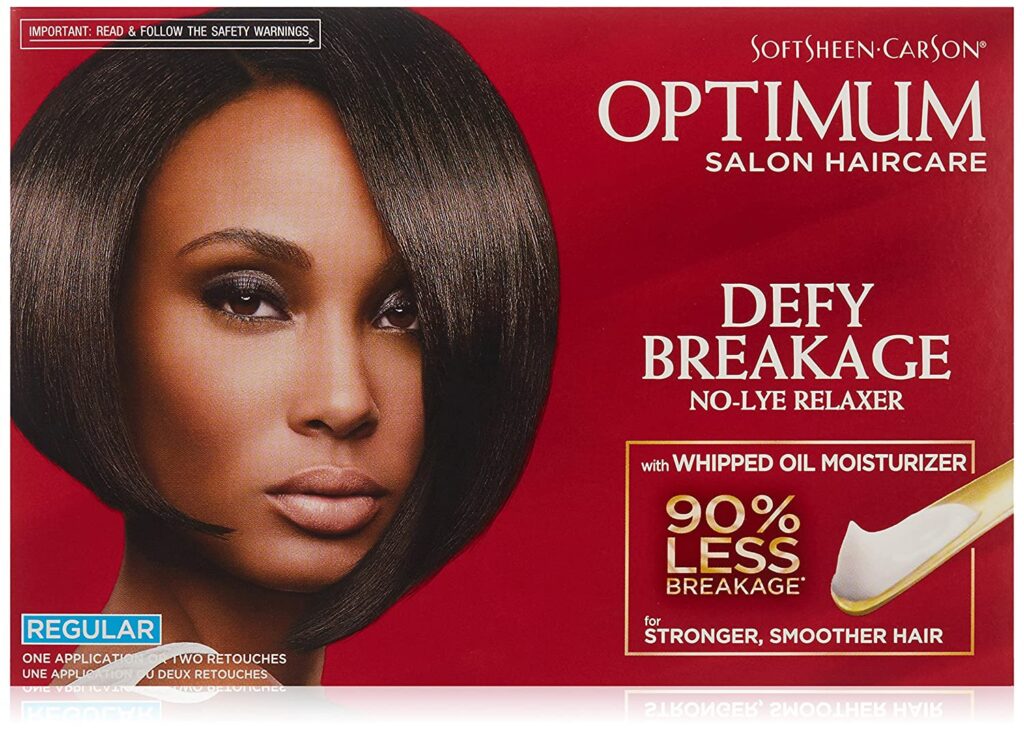

Recent and not-so-recent studies have linked hair relaxers to a host of female cancers and other reproductive health issues such as uterine fibroids.

A recent study from the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology in Kumasi, Ghana, linked hair relaxers to breast cancer in Ghanaian women.

They noted even higher risks for those who used them longer and those who mainly used no-lye products. In the United States, many hair relaxer companies have had lawsuits brought against them because of their link to cancers.

Some of you may be thinking: “Our mothers and grandmothers used relaxers for years and lived to a ripe old age” or “something must kill a man” or even “ all die be die” – the phrase popularized by former Ghanaian President Nana Akufo-Addo meaning simply, “All deaths are equal.”

And while that may be the case, African women deserve to know the risks associated with the use of hair relaxers so they can make informed decisions about their health.

This op-ed intends to do just that – to lay out the facts about the effects of prolonged hair relaxer use, hoping that at least one person who can, will decide to ditch this one proven way to cancer.

It doesn’t exalt those with natural hair, nor does it disparage those who choose to relax their hair.

I stopped relaxing my hair when I was 9 years old. In Ghana, almost everyone has to cut their hair for high school. I cried and moaned the loss of my long “flowy” hair, but I had little control over the situation.

The natural hair movement was just gaining momentum by the time I entered university, and I had a dream of growing my natural hair long and thick.

This lasted a few months until my father asked why my hair was “sakatuuu” aka “kinky”. While I did call out his bias and accuse him of a colonizer’s mentality, I caved and got my hair permed a few weeks later.

Even then, I had a love-hate relationship with my permed hair. My fine and thin 4C textured hair, when permed, was often so soft and light that I had to keep it in a ponytail, or it would “obey the wind”, as they say.

I also hated the cuts the chemical relaxers would leave on my sensitive scalp, even when I used the milder children’s relaxers.

Worst of all, I hated having to sit in the hot dryer after having my hair and scalp tortured, and all for what? Straight, more “manageable”, socially accepted hair?

In 2019, I finally made the difficult but empowering decision to do the so-called “Big Chop”, where I cut off all my relaxed hair, leaving my natural hair to flourish.

As African women, we are constantly reminded about how the “health cards” are stacked against us. How we are more likely to develop fibroids, uterine cancers, breast cancers, and many other forms of cancers compared to other demographics.

Why add to this imbalance by using hair relaxers that contain the very chemicals that have been proven through numerous studies to contribute to cancer?

As a way forward, these are my recommendations:

- All hair relaxers should have a warning label – similar to the label on cigarettes – that clearly states the risk of developing cancers with prolonged use.

- A comprehensive and far-reaching public campaign to sensitize African women to the risks of prolonged relaxer use.

- A minimum age (recommended 16) at which young women, armed with knowledge about the cancer risks associated with the use of hair relaxers, can make an informed decision about whether or not to perm their hair. This is to ensure that the decision to perm one’s hair is made only after a risk and benefits analysis. This way, hair perming will be a deliberate informed choice, not one made for them by a parent or out of insufficient knowledge.

This three-pronged approach can help reduce the risk of cancers associated with the use of hair relaxers disproportionately affecting us, African women.

Why do cigarettes get to have a warning label, but hair relaxers do not? Is there something specific we need to do to push for the FDA/Standards Board to provide information to us? To the hairdressers’ associations?

This is a loud call for African women to be given the courtesy of widespread and accessible education on the potential risks of some commonly accepted beauty practices, including the use of hair relaxers to chemically straighten hair for personal or professional reasons.

It is a call for conscious and informed decision-making by African women.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Labari Journal. This content represents the author’s perspective and analysis.