GLO-DJIGBÉ, Benin — Benin is a country that has often been overlooked in the shadow of its giant neighbor, Nigeria.

According to estimates, the West African nation has a population of about 14 million people compared to Nigeria’s 234 million or even Ghana’s 33 million.

But despite its population, Benin is ready to flex its muscle as it embarks on one of its most ambitious projects.

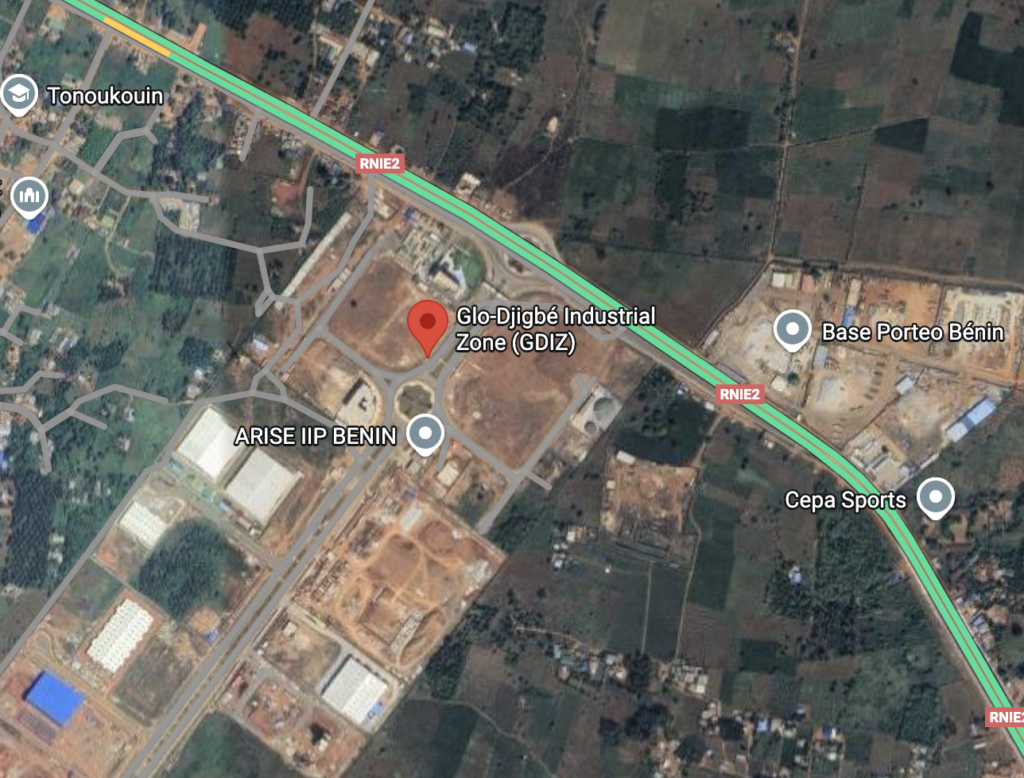

Under the direction of President Patrice Talon—the former “Cotton King” turned technocratic leader—the country is building the Glo-Djigbé Industrial Zone (GDIZ).

The project is a $20 billion “productive city” designed to serve as a massive escape hatch from the aging, flood-stricken capital of Cotonou and a final break from the country’s history as a raw material exporter.

However, the project has drawn a lot of scrutiny due to potential affiliations with controversial tech investor Peter Thiel, a platform called Prospera Africa, and the “charter city” movement.

The “New City” Strategy

For decades, Benin’s economy has been trapped in a colonial-era loop: it grows the world’s finest cotton and cashews, ships them off to be processed, and buys them back as finished goods.

President Talon’s “Revealing Benin” program seeks to end this cycle by creating an integrated ecosystem where the entire value chain remains within the country’s borders.

“The programme involves a scale of investment never before seen in the country, and is designed to boost employment, improve public well-being, create wealth and raise Benin’s international profile,” said President Talon in a statement in an official document.

The 1,640-hectare site is marketed as a “Work, Live, Learn, and Play” community.

It is being outfitted with “smart” infrastructure, independent power grids, and its own administrative “single window” to bypass the bureaucracy that often stifles African business.

The Shadow of the “Charter City”: Próspera and Peter Thiel

The project has taken on a new dimension as Benin becomes a focal point for libertarian-leaning investors interested in “startup cities.”

Central to this conversation is Próspera, a governance platform famously backed by billionaire Peter Thiel and venture capital firms like Pronomos Capital.

The group set up its first project in the South American country of Honduras. Its next project appears to be in the Africa region, with Prospera Africa, which was being run by Magatte Wade, a Senegalese-born entrepreneur raised in France.

While Benin’s projects are officially public-private partnerships with Arise IIP, the “Próspera model”—which advocates for semi-autonomous zones with their own legal and regulatory frameworks—is the invisible hand guiding the logic of Glo-Djigbé.

Pronomos Capital, backed by Thiel and Marc Andreessen, has been scouting for “Prosperous Cities” across Africa.

Their goal is to invest in jurisdictions that operate under a “digital free zone” or charter model, allowing for rapid innovation in biotech, fintech, and manufacturing without the drag of traditional state regulation.

By creating a city with 100% capital gains tax exemptions and independent dispute resolution, Benin is effectively creating a “state within a state.”

Lawsuit Against Prospera

Ms. Wade’s partnership with Prospera appears to have soured when she announced she was suing the firm. She alleges that executives falsely told her business contacts she had committed crimes and attempted to embezzle over a million dollars after her resignation. (Ms. Wade reportedly resigned last September.)

The lawsuit claims CEO Erick Brimen, along with other executives, then launched a concerted effort to destroy her reputation.

They allegedly convened a board meeting during her best friend’s funeral and began telling her African contacts, including Ugandan stakeholders Robert Kirunda and Kwame Rugunda, that she had “crossed critical lines” and likely committed crimes.

They pointed to a proposed “2025 IP Assignment”—a good-faith attempt, Wade says, to formally separate her intellectual property from the company—as evidence of misconduct.

The lawsuit is currently pending in court.

The Price of Autonomy

The involvement of such high-profile, “disruptive” investors has made the project a lightning rod for controversy.

To critics, these are not just industrial zones; they are “islands of prosperity” that risk operating outside the reach of democratic accountability.

The most immediate cost has been felt by the local population.

In 2025, workers at a cotton factory in the GDIZ decried “slave labor” hours and detailed harsh working conditions.

“We produce 1,000 to 1,200 garments a day. In an eight-hour shift, we can sew 700 to 900 polo shirts. Every day, they push us to go further. The conditions are miserable. Wages are too low,” one worker said in an interview with the media organisation, People’s Dispatch.

In a political climate where dissent is increasingly restricted, many fear that the “New Benin” is being built for global capital, rather than the average citizen.

“We are not working for Benin. We are working for foreigners,” one worker said.

“They profit, but we go hungry. If they truly wanted to industrialize this country, they would also improve our lives so that we could feed our families. That is all we ask.”

A High-Stakes Gamble

Benin’s gamble is massive. The country has issued billions in Eurobonds to fund the infrastructure, betting that the productivity of Glo-Djigbé will eventually pay off the debt.

If the gamble works, Benin could become the “Dubai of West Africa”—a high-tech, industrial powerhouse that provides 300,000 jobs and a roadmap for its neighbors.

If it fails, the country may find itself burdened with debt and “ghost cities” that belong more to its foreign investors than to the people of Benin.