ACCRA, Ghana — In the world of stand-up comedy, timing is everything. But for OB Amponsah, one of Ghana’s most celebrated comics, the latest timing to hit his desk wasn’t a cue for a joke—it was a tax bill.

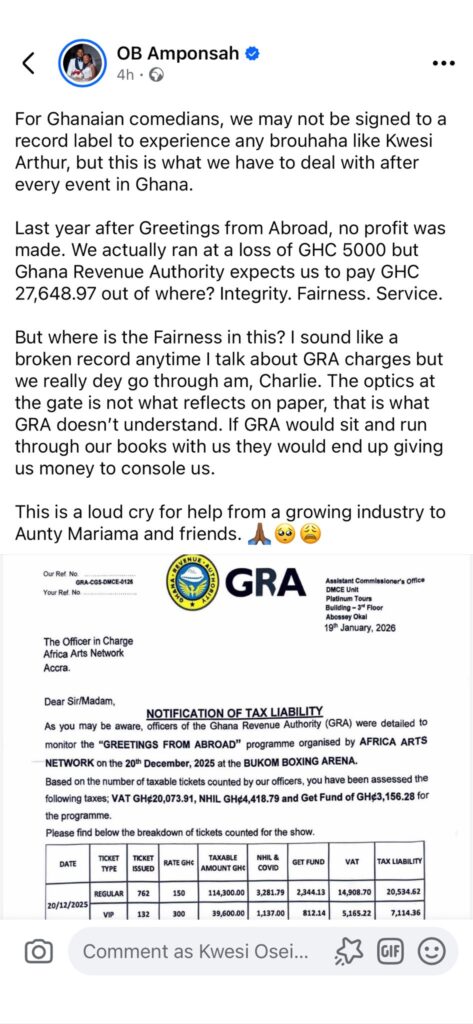

Following the “Greetings From Abroad” comedy show held this past December, the organizers, Africa Arts Network (AAN), were served with a Value Added Tax (VAT) assessment of GHS 27,648.97.

The reaction from the creative camp was swift and visceral. Taking to Facebook, Amponsah and his colleagues questioned the integrity and fairness of the Ghana Revenue Authority (GRA), citing a painful irony: the show had actually recorded a loss of GHS 5,000.

“We actually ran at a loss,” the comedian reportedly lamented, “but GRA expects us to pay… out of where?”

The public outcry has ignited a fierce debate in Accra’s vibrant creative arts scene, pitting the “starving artist” narrative against the rigid machinery of national revenue mobilization.

However, according to tax experts, the comedian’s grievance may be based on a fundamental misunderstanding of how the law works.

The “Agent” Problem

In a detailed post in response to Mr. Amponsah, Kwesi Osei Breman, a Chartered Accountant and Tax Practitioner, found himself in the role of an educator.

In a detailed rebuttal to the comedians, Breman argued that while the emotional distress of losing money on a production is real, “tax is law, and the law does not recognize sentiments.”

The crux of the issue lies in the difference between Corporate Income Tax (CIT) and Value Added Tax (VAT):

- CIT is a tax on profit. If you lose money, you don’t pay.

- VAT is a consumption tax. The business is merely a “conduit” or agent for the government.

“The GRA is not asking AAN to pay tax on the show’s profit,” Breman explained. “It is requesting the VAT collected on the tickets.”

According to the audit, the show moved GHS 153,900 in taxable ticket sales. By law, that money should have included a VAT component collected from the audience members at the point of sale.

A Regulatory Tightrope

The dispute highlights a growing friction point in Ghana’s economy: the formalization of the informal and creative sectors. Under the VAT Act 2013 (Act 870), event promoters are required to register for VAT at least 48 hours before a show if sales are expected to exceed GHS 10,000.

For many in the arts, these regulations feel like a “stifling” of growth. For the state, they are the necessary plumbing of a functioning economy.

Breman points out that the organizers now face a race against the clock. Under the Revenue Administration Act, failing to settle the bill by January 31, 2026, could trigger punitive interest rates—calculated at 125% of the statutory rate, compounded monthly.

A Lesson for the Limelight

The saga of “Greetings From Abroad” is serving as a high-profile case study for the entire Ghanaian entertainment industry. The message from the accounting community is clear: creatives can no longer afford to treat tax compliance as an afterthought.

“This case presents a unique opportunity for event promoters and creatives to factor tax planning into their pricing decisions,” Breman noted.

In short, if you don’t add the tax to the ticket price at the beginning, you’ll end up paying it out of your own pocket at the end—even if the curtains close on a deficit.

As the January 31 deadline looms, the comedy community is learning a lesson that is anything but funny: in the eyes of the taxman, the show must go on—but only after the state gets its cut.

This article was edited with AI and reviewed by human editors