On Tuesday, February 18, 2025, Juliet Asante, the former Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of Ghana National Film Authority (NFA), logged onto Facebook to share her working experience and to extend best wishes to her successor.

Her post soon became a revelation of an inappropriate incident she experienced while in office.

In the post, she described how two male colleagues unprofessionally subjected her to inappropriate behaviour at the workplace.

According to her, one of her colleagues physically lifted her off the ground and shoved her into the arms of another, who insisted on “hugging” her.

From her narration, this was all done without her consent.

To make matters worse, one of the men during the incident said to her, “Maybe, I am the one who will marry you one day.”

Ms. Asante stated how she felt “dirty” afterward, recounting that she scrubbed herself vigorously in the shower until “her skin was tender” after the incident.

The post attracted responses from many, including the current CEO of the NFA, Kafui Danku, who offered sympathies, saying her organisation will “definitely reach out to her on the matter.”

Others questioned the timing of her post, asking on social media, “Why didn’t she resign then?”

Ms. Asante did not state whether she reported the incident or received any apology from her colleagues.

Unfortunately, her experience is not an isolated incident at the Ghanaian workplace.

There have been recent reports and investigative stories written over the years revealing the experiences of victims, especially women, who have been subjected to what could best be described as sexual harassment.

A study among nurses in Ghana revealed that 43.6% experienced sexual harassment. The primary perpetrators included male physicians, male nurses, male relatives of patients, and male patients.

Sexual harassment can take many forms, including unwanted advances, crude or sexual comments, all of which contribute to an intimidating or hostile work environment.

In Ghana, laws have been enacted to penalize perpetrators who commit sexual harassment offenses.

Ghana’s Labor Act of 2003 defines sexual harassment as “any unwelcome, offensive or importunate sexual advances or request made by an employer or superior officer or a co-worker to a worker”.

The Act mandates employers to investigate cases of harassment. Culprits found guilty face the possibility of employment termination.

However, many individuals who experience sexual harassment at work choose not to speak out for various reasons, some of which are explored in this story.

I think culturally it’s not a thing women here are empowered to do”.

A victim on why there are not more reports on sexual harassment in Ghanaian workplaces

Prevalence of Sexual Harassment in Workplaces

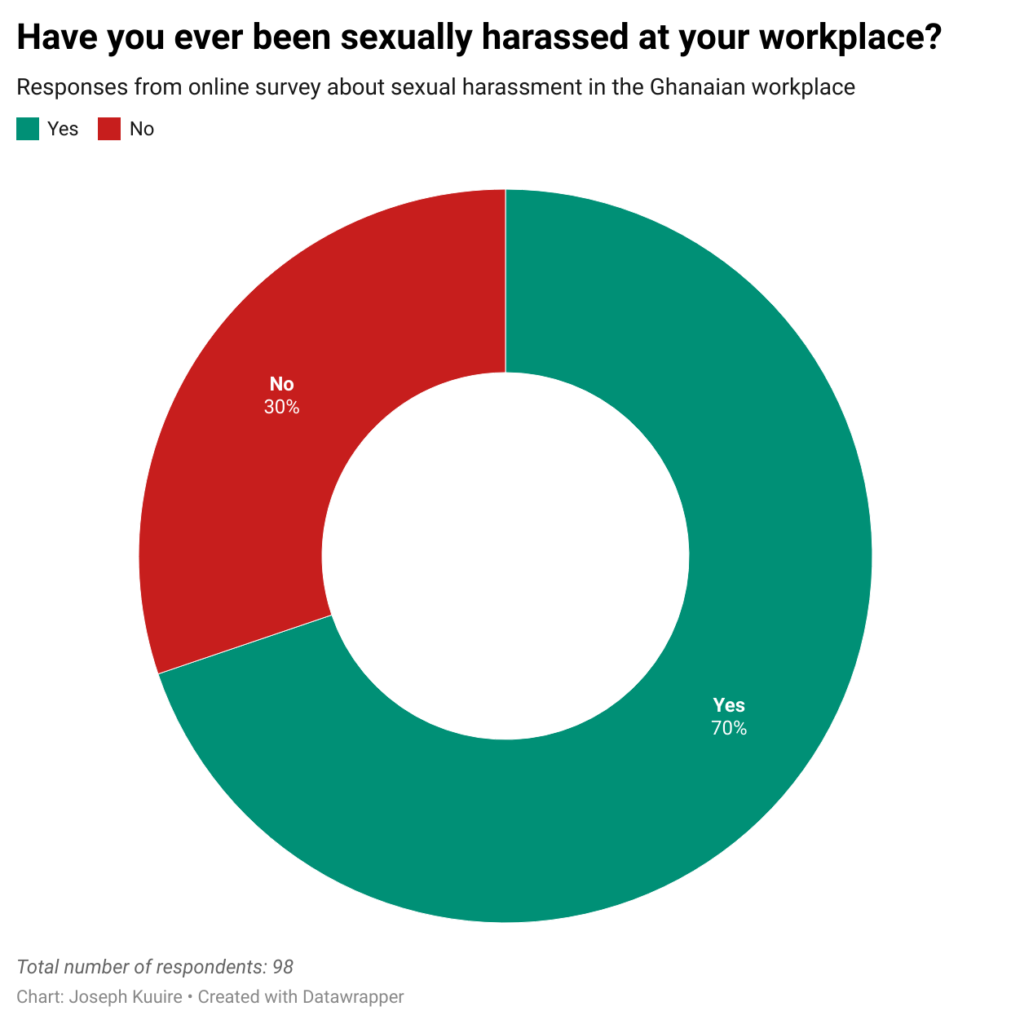

An online survey conducted by The Labari Journal between February and March 2025 to learn more about sexual harassment in Ghanaian workplaces showed that out of 98 respondents, 70% had experienced sexual harassment in their work environment.

Victims interviewed for this story highlighted themes of toxic workplaces where male co-workers and superiors frequently harassed female workers.

Ama (not her real name), who was interviewed online for this story, shared how a male colleague continuously harassed her with unsolicited sexual text messages after working hours.

“Even after asking him to stop, he persisted. He started to bring the conversations into the workplace which was extremely uncomfortable,” she said.

She also shared how the same colleague was harassing another female worker.

“Our office receptionist broke down and confided in me and it turned out he was doing the same to her,” she revealed.

Another victim, Jennifer (real name concealed), spoke about how the CEO of her workplace repeatedly made unsolicited comments about her appearance and that of other female employees.

“It made me uncomfortable”, she said. “It made me wonder if there were ulterior motives involved in this and why he felt the need to do this to me and several women in the organization.”

When asked why she or no one else chose to report, especially when there was a written policy against harassment, she said, “I think culturally it’s not a thing women here are empowered to do”.

Other victims interviewed expressed similar sentiments about not reporting harassment incidents.

Another victim named Barbara (not her real name) stated that she withdrew her complaint, fearing backlash.

“I was scared of repercussions so I asked for no action to be taken,” she said, revealing that she had to request absence from her workplace after reporting an incident.

Michelle (real name withheld) said she was “laughed off” after filing a complaint at work.

“It’s all jokes here, that’s how we joke,” was the response she received after reporting.

The Ministry for Gender, Children, and Social Protection of Ghana, which is a stakeholder in the formation of policies to address issues such as harassment, was contacted for comment on workplace harassment in the country.

It did not respond at the time of publication.

“There’s a lot of shame attached to being a victim, especially in our society where people often question what the victim was wearing, where they were, or why they didn’t fight back.”

Dr. Akosua Ampofo, a professor of African and Gender Studies at the University of Ghana

Patriarchy and Imbalance of Power Hold Back Victims

In an interview, Dr. Akosua Ampofo, a professor at the Institute of African Studies at the University of Ghana, explained that victims may hesitate to report workplace incidents due to power imbalances and the deep-rooted patriarchy in Ghanaian society.

According to her, patriarchy, defined as a social system in which men hold primary power and dominate in roles of leadership and social privilege, plays a significant role in silencing individuals and discouraging them from speaking out publicly.

“The person with less power is less likely to either report or to see it through because they are afraid that there will be repercussions against them.

“The perpetrator can decide to use the power that they have to either to say that they are lying, eradicate your report, or pack the investigative panel with their friends,” she added.

Dr. Ampofo also argued that current society trends tend to place more blame on the victim if they decide to report incidents like sexual harassment.

“There’s a lot of shame attached to being a victim, especially in our society where people often question what the victim was wearing, where they were, or why they didn’t fight back.”

The professor also noted that the imbalance of power makes it difficult to hold sexual harassment perpetrators accountable.

“When the perpetrator is someone in a position of power—a boss, a lecturer, a respected figure—reporting can feel impossible because victims fear losing their job, their education, or even their reputation.”, she said.

“Many [victims] have had to resign from their job reluctantly as it had become unbearable. Many times, they are National service Personnel or interns who don’t feel they have a voice.”

Billie Richardson, a life coach and psychotherapist

The Mental Toll Sexual Harassment Has On Victims

In an interview with Billie Richardson, a life coach and psychotherapist, she explained that sexual harassment in the workplace can have adverse effects on the mental health of workers.

“A toxic work environment can lead to disengagement and lack of productivity and even resigning”, she said. “Victims can feel overwhelmed, anxious, or depressed.”

She further added that victims can experience Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), which manifests in the form of nightmares and emotional numbness in some individuals.

“In some cases, the trauma and anxiety associated with sexual harassment can manifest as agoraphobia, where they develop a fear of public places or situations where they might feel unsafe or unable to escape”, she said.

Ms. Richardson, who was part of an Employee Assistance Program (EAP) providing support to victims of sexual harassment, said some workers had to leave their jobs due to continued harassment.

“Many [victims] have had to resign from their job reluctantly as it had become unbearable. Many times, they are National service Personnel or interns who don’t feel they have a voice.”

According to her, individuals who tried to lodge complaints of harassment were often disbelieved and felt unsupported, leading to worsening PTSD.

“Many feel unsupported by Human Resource (HR) departments and struggle with prolonged emotional distress, leading some to resign or suffer in silence,” she explained.

Can Ghana Do More For Victims?

Ms. Richardson stated that although companies have implemented sexual harassment policies, they are not always applying or enforcing them.

“Companies need to implement strict anti-harassment policies to create a zero-tolerance workplace culture as well as provide EAPs for counseling and peer support groups,” she said.

She added that more mandatory training sessions and anonymous reporting channels should be considered to help ensure victims report harassment without fear of retaliation.

She also advocated broader public discourse on sexual harassment in Ghana, not just in the workplace but in society.

“Public discourse plays a critical role in shaping mental health awareness and workplace policies related to sexual harassment in Ghana.

As conversations about this issue gain visibility, they influence how society perceives, addresses, and responds to harassment, leading to policy reforms, cultural shifts, and improved support systems for victims,” she said.

As Dr. Ampofo highlighted earlier, patriarchy remains deeply embedded in our society. While laws exist to support victims, a culture still shaped by patriarchal norms will continue to discourage them from seeking justice.

Employers could implement suggestions from psychotherapist Billie Richardson, including stricter policies, enforcement, and anonymous reporting to cultivate a better working environment.

But until Ghana confronts its deep-rooted patriarchy and power imbalances directly, sexual harassment complaints will persist as mere ‘jokes’—though for victims, the mental health fallout is anything but funny.