Illegal gold mining, or more popularly known as “Galamsey” in Ghana, has been a sore spot for the Western African nation.

Former President Akufo-Addo, in a speech, stated he would put his presidency on the line to combat the menace.

But his promises feel short as more water bodies witnessed more pollution from galamsey, with water turbidity levels increasing and becoming unsafe for drinking in some communities.

Now, the newly established Ghana Gold Board, known as GoldBod, from the Mahama administration, is exploring a technological fix that could make every ounce of the country’s gold traceable from pit to port — using blockchain technology.

Officials believe the system could mark a turning point in the fight against illegal mining, known locally as galamsey, which has devastated landscapes.

A Digital Ledger for Every Gram

According to Sammy Gyamfi, the current CEO of GoldBod, they will be rolling out the new technology in the first quarter of 2026.

“We have given timelines that by the first quarter of next year, we will have a track-and-trace system, which has never happened since Ghana became Ghana,” Mr. Gyamfi stated in an interview last week.

“This system will allow us to trace every gram of gold produced in Ghana and purchased by the Gold Board to its source.”

So, how will this new system work? Although GoldBod hasn’t given detailed information about the system, we can run a thought experiment:

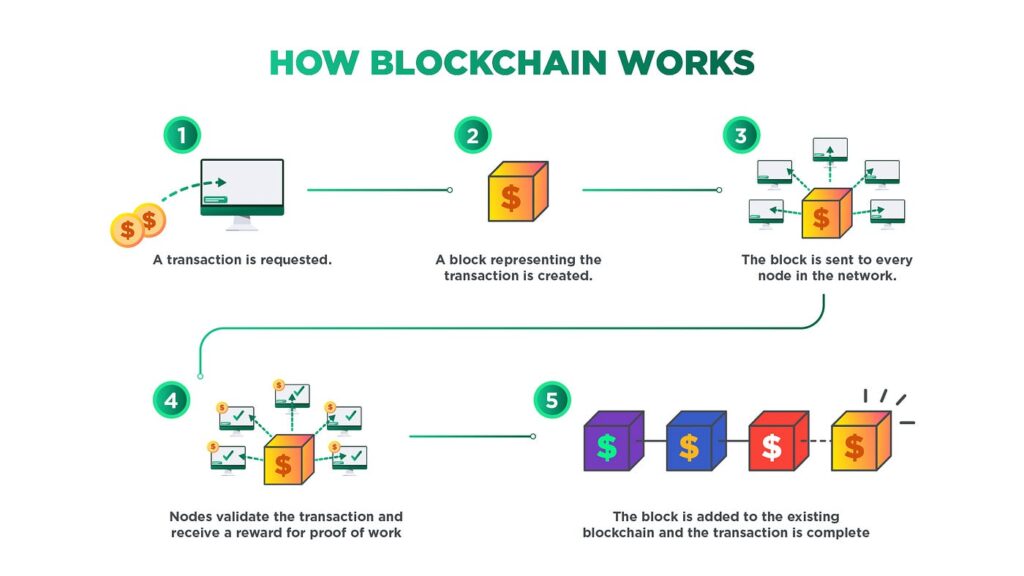

GoldBod’s proposal would essentially be a digital ledger system, built on blockchain — the same technology behind cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin, but repurposed for commodity traceability.

Each batch of gold produced in Ghana would be assigned a unique digital identity, linking it to its geographic origin, the miner who extracted it, and the licensed buyer who purchased it.

When the gold moves — from a small-scale mining site to a refinery, then to an exporter — every transaction would be recorded as a new, time-stamped “block” on the shared ledger. Once added, it cannot be altered or erased.

By embedding data integrity into every stage of production, unregistered gold would have no valid blockchain record — and therefore, no path to legal export.

Building and Rolling Out the Infrastructure

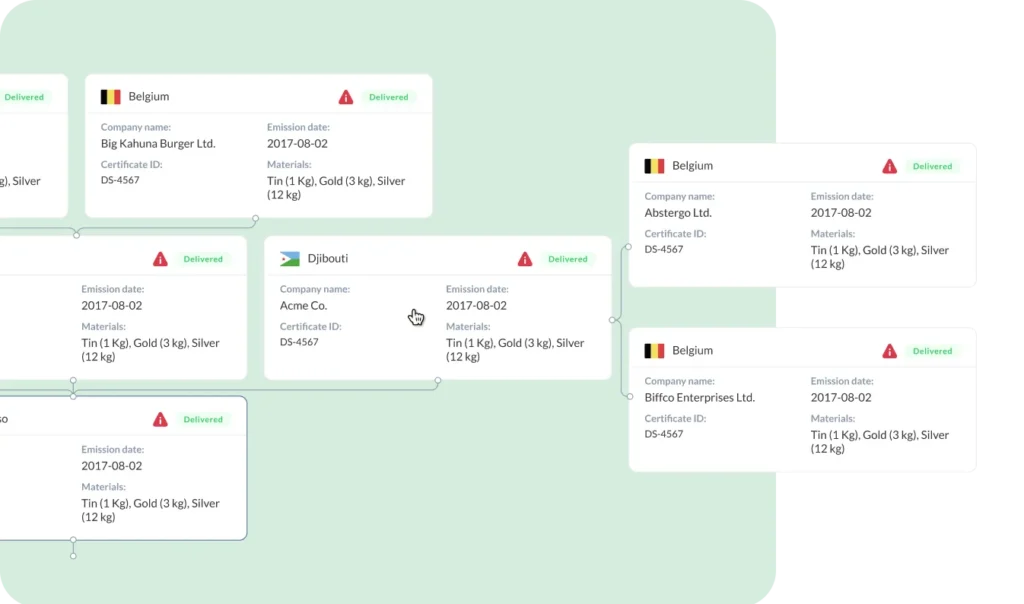

To make this vision real, GoldBod would either use an in-house team or contract a company to design a three-tier architecture that could link small-scale miners, regulators, and exporters into one digital ecosystem.

- Mobile Mining App – Small-scale miners and licensed buyers would use a smartphone app to register gold batches, capturing GPS coordinates, photos, weights, and license details. Each batch would receive a QR code or RFID tag for tracking.

- Assay and Refinery Integration – Certified assay labs, such as those operated by the Precious Minerals Marketing Company (PMMC), would upload purity tests directly into the system. Each assay report would be cryptographically signed and attached to the batch record.

- Permissioned Blockchain Network – Instead of a public blockchain, Ghana would use a permissioned network where only authorized entities — GoldBod, PMMC, the Minerals Commission, refineries, and customs — can add or verify data.

Lessons from Abroad

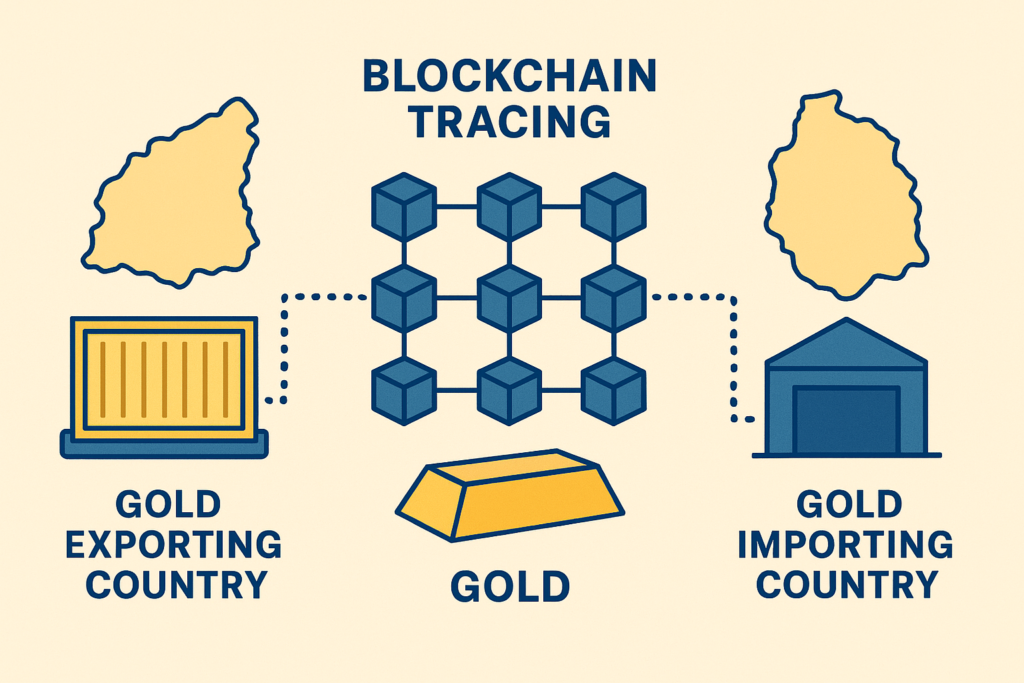

Some countries have already experimented with blockchain to track gold exports and mining.

Fênix DTVM, a Brazilian company, is using blockchain technology in partnership with a blockchain-based traceability system called Minespider that helps companies track raw materials.

In Dubai, the Dubai Multi Commodities Centre (DMCC), a free zone authority in the emirate, completed a deal for a precious metals refinery and storage facility enabled by blockchain technology.

If Ghana is successful in adopting a similar solution, it could be an effective tool in combating illegal mining and tracing its gold exports.

Potential Pitfalls

Some caution that technology alone won’t solve deep-rooted governance issues.

Christina Miller, owner of a sustainable jewelry consulting service and who works for the nonprofit Amazon Aid, said the use of Blockchain won’t necessarily lead to responsible mining.

“Blockchain isn’t synonymous with responsible mining,” She said in a 2023 interview with Mongabay, a non-profit media organisation.

“It just tells you that a purchase was made and ownership of the goods was transferred along a documented path.”

Connectivity gaps, cost, and resistance from informal miners also pose challenges.

Implementing blockchain traceability across thousands of small miners and buying agents would require smartphones, internet access, tamper-proof tags, and digital training — all of which can be expensive and logistically difficult.

With blockchain, GoldBod is betting that transparency can become the country’s new competitive edge.

Mr. Gyamfi stated earlier in the year that some pilot projects in selected mining communities have already begun, and the results have been encouraging.

This article was edited with AI and reviewed by human editors