On November 7th, 2025, President John Dramani Mahama announced a new bold initiative to build a new clean, smart, and green city.

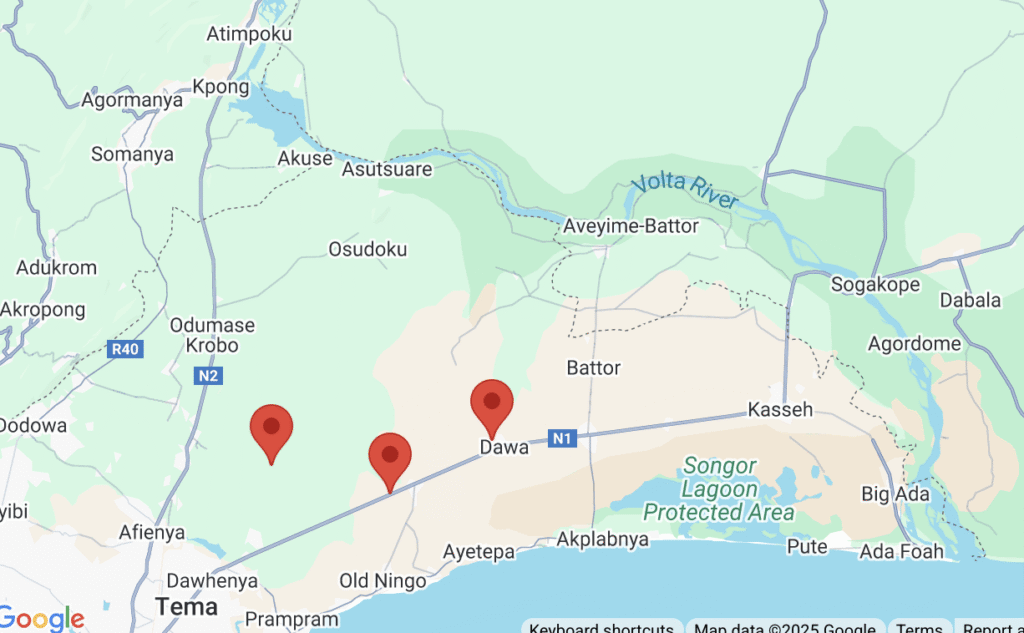

Called the “Green City Project“, it will be a sprawling 20-year urban plan that would stretch from the Saglemi Housing enclave through the Bondase Military Range, connecting the Volta and Eastern regions.

It would have orderly streets, smart drainage, industrial parks, and modern housing — “a city without kiosks or containers,” the President said.

For many in Ghana, the announcement sounded familiar.

Sense of Deja Vu

Twelve years ago, another ambitious city was announced with similar fanfare. It was called Hope City. The proposed initiative was a glittering futuristic tech hub planned for Prampram, east of Accra.

The project was launched on 4th March 2013. It was a partnership between the government and state-owned technology company RLG Communication. Microsoft is also reported to be collaborating on the development.

The project was reported to cost an estimated $1o billion.

“What we are trying to do here is to develop the apps [applications] from scratch,” Roland Agambire, head of RLG Communications, said in an interview with the BBC.

“This will enable us to have the biggest assembling plant in the world to assemble various products – over one million within a day.”

Ultimately, the project never took off.

The fields near Prampram remain mostly empty today, a reminder of how quickly big dreams can evaporate in Ghana’s thin air of bureaucracy and political change.

So when President Mahama announced a new city project this month, the sense of déjà vu was palpable.

Promise of Something New

Described as a 20-year project, the Green City will stretch from the Dawa Industrial Zone, incorporating the Saglemi Housing Estate, through the Bundase Military Range, into the Volta and Eastern regions.

“This will be a new city that will attract investment, it will attract tourism, it will be a smart city,” President Mahama said at a sod cutting ceremony for a new 200MWp Solar for Industries (SFI) project.

“It will have a modern drainage system, it will have good sanitation, there will be no kiosks and containers in that city, and people will not be walking by the roadside,” he added.

According to the President, the feasibility study and design for the city are set to commence by the end of the year, with the Minister of Finance making budgetary provisions for the initial phases.

The President told reporters that Ghana’s capital, Accra, has become unmanageable, and the new initiative will help future generations.

“We must plan for the future. The Green City will offer a more sustainable, livable environment for the next generation.”

Fool Me Twice?

Ghana’s capital, Accra, is facing numerous challenges.

The city’s population has nearly doubled in two decades, swelling past five million people.

Traffic jams have intensified, and new housing developments compete with neglected drainage systems that flood every rainy season.

For years, policymakers have floated grand solutions to relieve the capital’s mounting pressure. Yet few of those ideas have materialized beyond blueprints and ribbon cuttings.

Other grandiose projects announced within the city have also faced challenges.

Marine Drive Accra, a flagship urban initiative aimed at transforming Ghana’s capital into a world-class tourism and economic hub, struggled with funding since it was announced in 2017 by the Akufo-Addo administration.

The project was estimated to be over $1 billion. The new Mahama administration has pledged to continue the project.

The question that hovers over the new Green City plan is one Ghanaians have learned to ask: Will it actually happen?

Government officials say the new initiative will take a phased approach — focusing first on feasibility, infrastructure, and partnerships before breaking ground.

There are also signs that Mahama’s team wants to court a wider pool of investors, including local developers and international partners from China and the Gulf.

Ghana’s record for large-scale projects is mixed, with projects like the Saglemi Housing Project — ironically located just a few kilometers from the proposed Green City site — remaining half-built and mired in court cases over mismanagement.

Hope City 2.0?

For now, the Green City exists only on paper. The feasibility studies will take months. Designs could take years. Construction, if it begins at all, may not start until 2028.

Large-scale projects like this also tend to stall or be abandoned after political change. If there is a change of government after 2028, there is no guarantee that the project will continue.

Whether this project takes over remains to be seen. Administrations over the years have made similar pledges, with Hope City being the biggest flop in the last 20 years.

It’s too early to say whether the Green City project will be a Hope City 2.0. But skepticism around its completion is not too far-fetched.