LAGOS, Nigeria — In the bustling markets of Lagos and the overflowing classrooms of Enugu, Nigerian women are the undeniable engine of the nation’s daily life. They own 33% of the country’s micro-businesses, make up half of the secondary school teaching workforce, and staff the frontlines of the healthcare system.

Yet, gaze upward to the halls of power where the decisions governing their lives are made, and women virtually disappear.

A sweeping new report, The State of Women’s Leadership Report 2025, released by the Women in Leadership Advancement Network (WILAN), reveals a nation grappling with a stark “XX Paradox”: women deliver the bulk of the nation’s service and labor, yet remain systematically excluded from its leadership.

“What this report presents is a snapshot of women’s representation… that reveals both the promise and the gaps,” writes Abosede George-Ogan, the founder of WILAN.

“The data is clear. Women are not underperforming; they are underrepresented,” said Nafisa Atiku-Adejuwon, WILAN Board member.

Nations that prioritise gender-balanced leadership are more prosperous and stable. This report provides a benchmark that leaders can use to make progress intentional, visible, and measurable.”

The data paints a picture of a country where leadership remains coded as male, with progress flourishing only in sectors where distinct rules or strict meritocracies force the door open.

The 4 Percent Problem

Nowhere is the exclusion more visible than in Nigeria’s legislative chambers.

In the 10th National Assembly, inaugurated after the 2023 elections, women occupy a mere 4.5 percent of seats.

Out of 469 federal lawmakers, only 21 are women—four in the Senate and 17 in the House of Representatives. This figure places Nigeria far below the African average and at the bottom tier of global rankings.

The situation is equally grim at the state level. Across the 36 states, women hold less than 5 percent of House of Assembly seats.

In 14 states—including Kano, Bauchi, and Rivers—state legislatures are entirely male, without a single female voice to shape local laws.

The executive branch offers little reprieve.

Nigeria has never elected a female governor. While appointed roles offer a potential bypass to the rigors of electoral politics, they too reflect deep disparities.

Only eight of President Bola Tinubu’s 48 ministers are women. At the state level, only Kwara State has met the country’s National Gender Policy benchmark of 35% representation, boasting a cabinet that is 46% female.

The ‘XX Paradox’ in Health and Education

Perhaps the most jarring findings come from the sectors traditionally associated with women: health and education. The report identifies this as the “XX Paradox”—sectors where women dominate the workforce but vanish at the executive level.

In healthcare, women constitute the vast majority of nurses and midwives. Yet, the Nigerian Medical Association (NMA) has elected only one female president in its 65-year history. Currently, 99% of the NMA’s leadership is comprised of males.

“Women deliver most of the services yet rarely shape the decisions,” the report notes.

A similar disconnect plagues academia.

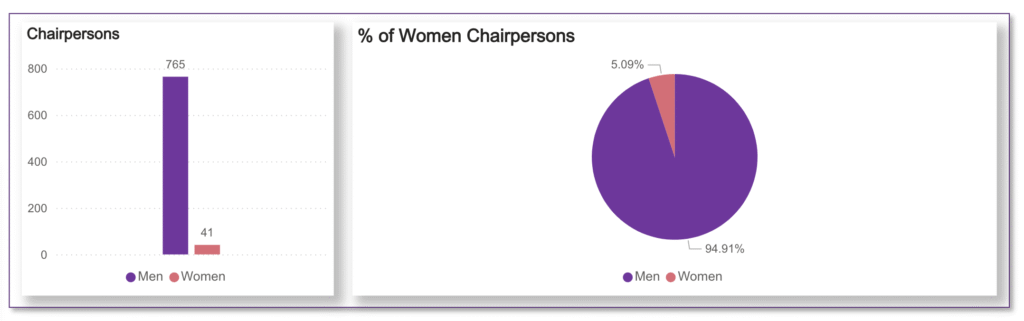

While women make up a significant portion of the teaching staff, only 12 of Nigeria’s 270 university Vice Chancellors are women. Since independence, over 720 individuals have held this top academic post; only 38 have been women.

| Sector | Female Representation |

| Micro-Businesses | 33% |

| Judiciary (State Heads) | 41% (15 of 36) |

| Private Sector Board Seats | 31% |

| National Assembly | 4.5% |

| State Governors | 0% |

Where Structure Exists, Women Rise

The report offers a counter-narrative to the idea that women are unqualified or unwilling to lead. In sectors where advancement is based on professional tenure or enforced by regulation, women are thriving.

The Nigerian judiciary stands out as a beacon of inclusion. The Chief Justice of Nigeria, Justice Kudirat Kekere-Ekun, is a woman, and women head the judiciary in 15 of the 36 states.

At the Court of Appeal, women hold nearly 40 percent of the seats.

Why the difference? The judiciary relies on a structured career path where promotion is often determined by seniority and service records rather than the volatile and capital-intensive nature of political campaigning.

Similarly, in the private sector, regulation has proven to be a powerful accelerator.

Among the top 50 companies listed on the Nigerian Exchange (NGX), women now hold 31% of board seats. This progress is largely driven by the financial sector, where Central Bank mandates enforce gender diversity.

“The judiciary demonstrates that structured systems of promotion make a difference,” the report argues. “The banking sector shows that policy plus accountability can change boardrooms”.

The ‘Reserved Seats’ Solution

To bridge the gap in politics, advocates are looking beyond voluntary party reforms to legislative mandates. The report highlights the “Reserved Seats for Women Bill” (2025) as a critical potential turning point.

The proposed bill aims to create 37 additional seats in the Senate and 37 in the House of Representatives exclusively for women.

If passed, projections suggest women’s representation in the National Assembly could leap from 4.6 percent to approximately 20 percent.

For a country grappling with economic volatility and social unrest, the exclusion of half the population from decision-making is not just a rights issue—it is a developmental brake.

As the report concludes, “When women lead, governance becomes more accountable, economies grow more inclusive, and societies prosper“.

Until the political machinery is retooled to mirror the meritocracy of the courts or the regulations of the banks, Nigeria’s women will likely remain the backbone of the nation, but rarely its head.

Read/Download the full report below:

This article was edited with AI and reviewed by human editors