As the world enters 2026, the global financial landscape is being disrupted by a new trend: the prediction market.

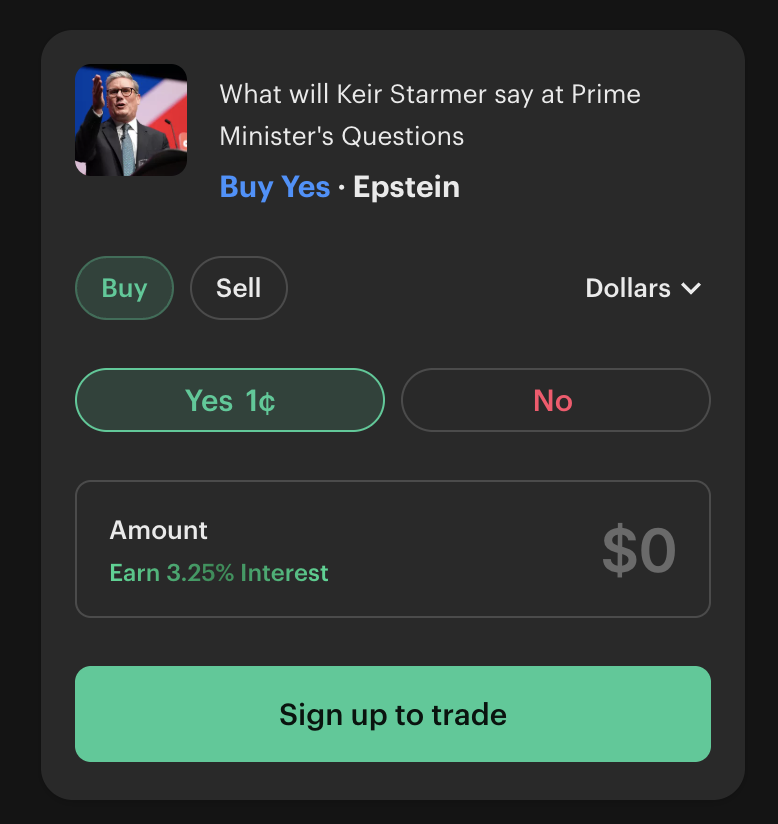

While betting platforms in Africa tend to focus more on sports, digital platforms like Polymarket and Kalshi allow users to trade on the outcome of almost anything. Users can bet on the outcome of an election or the length of a speech from a politician.

In 2025 alone, global prediction market volumes surged to over $44 billion, a staggering 130-fold increase from early 2024.

Although prediction markets are currently focused on markets like the US, the potential and opportunity for local players to jump on this trend in Africa cannot be ignored.

For Ghana and other African nations, public officials need to be more proactive than reactive when it comes to regulating these platforms.

If governments do not move quickly to regulate these “financialized” betting apps, they risk a new wave of addiction that wears the mask of “sophisticated investing.”

How Prediction Markets Work

At its core, a prediction market turns an uncertain future into a “tradable asset”.

In a prediction market, every question is turned into a binary option. A contract is created for an event—for example, “Will the Cedi appreciate against the Dollar by December 2026?”

The contract always pays out exactly $1 (or a fixed local equivalent) if the event happens. It pays out $0 if it does not.

The “magic” of the market is that the price of the contract reflects the collective “wisdom of the crowd.”

If the current price to buy a “Yes” share is $0.70, the market is signaling a 70% probability that the event will occur.

If new information surfaces (e.g., a favorable report from the Bank of Ghana), more people will buy “Yes” shares, pushing the price up to, say, $0.85 (an 85% probability).

Unlike a sports bet, where you place your money and wait for the final whistle, prediction markets allow for continuous trading.

If a user buys a share at $0.40 and the price rises to $0.70, they can sell the share to lock in their profit.

In traditional betting, users usually play against a “bookie”, whereas in prediction markets, you are trading against other people.

Why Prediction Markets are More Dangerous

The primary danger of prediction markets is their branding.

Traditional sports betting is widely recognized as gambling, carrying a certain social stigma.

Prediction markets, however, position themselves as “information aggregators” or “derivative trading platforms.”

For a young Ghanaian graduate struggling with unemployment, “betting on a football match” might feel like a vice, but “trading on geopolitical outcomes” feels more sophisticated.

This “gamblification” of finance lowers the psychological barrier to entry, drawing in demographics that might otherwise avoid the local betting shop.

Prediction markets are also leaning more into sports, with users being able to bet on specific sports events and their outcomes.

In New Zealand, the Department of Internal Affairs has stated that prediction market operators cannot offer what it considers gambling products to New Zealand residents under current laws.

They effectively stated that prediction markets are gambling.

A Continent at the Breaking Point

African governments are already fighting a losing battle against gambling addiction.

Recent data from 2024 and 2025 highlights a worrying trend. As of early 2025, 71% of Ghanaian youth reported having placed a bet. Across the continent, South Africa leads with 83%, followed by Kenya at 79%.

In Ghana, 74% of bettors cite “monetary motivation” as their primary reason for gambling. In a climate where youth unemployment is high at 15%, betting is no longer a hobby but rather a desperate (and failing) survival strategy.

A 2024 study in BMC Public Health found that 84% of young Ghanaian gamblers showed signs of problematic or moderate gambling behavior.

Even more alarming, 68.8% of these individuals reported clinical anxiety, and 43.6% suffered from depression.

Prediction market apps, which operate 24/7 and offer “instant liquidity,” are designed to exploit these exact vulnerabilities.

The Regulatory “Gray Zone”

Currently, most prediction markets operate in a legal vacuum in Africa.

They aren’t strictly sportsbooks, and they aren’t traditional stocks. Therefore, institutions, including the Gaming Commission and Securities and Exchange Commission, lack a clear mandate to regulate it.

This “regulatory arbitrage” could allow future prediction market apps to bypass limitations. They could bypass taxation, as many of them operate via cryptocurrency or offshore gateways.

Unlike the Ghana Stock Exchange, there are few rules preventing someone with “non-public information” from betting on a policy change, potentially leading to a rigged market where the average citizen always loses.

Proactive Governance

African governments cannot afford to wait for a crisis to act. A “wait and see” approach will result in a generation of youth whose capital and mental health have been drained by these new prediction market algorithms.

The Gaming Commission of Ghana and the SEC must co-author a framework that classifies prediction markets as a high-risk hybrid of gambling and derivatives.

Another initiative would be to have a prediction market platform, operating locally, to have a local representative.

Regulators should demand that these apps include “friction” (e.g., maximum deposit limits and mandatory risk warnings) similar to those used in regulated European financial markets.

Without swift regulation, prediction markets could accelerate a cycle of poverty and psychological distress that the continent might be ill-equipped to deal with.