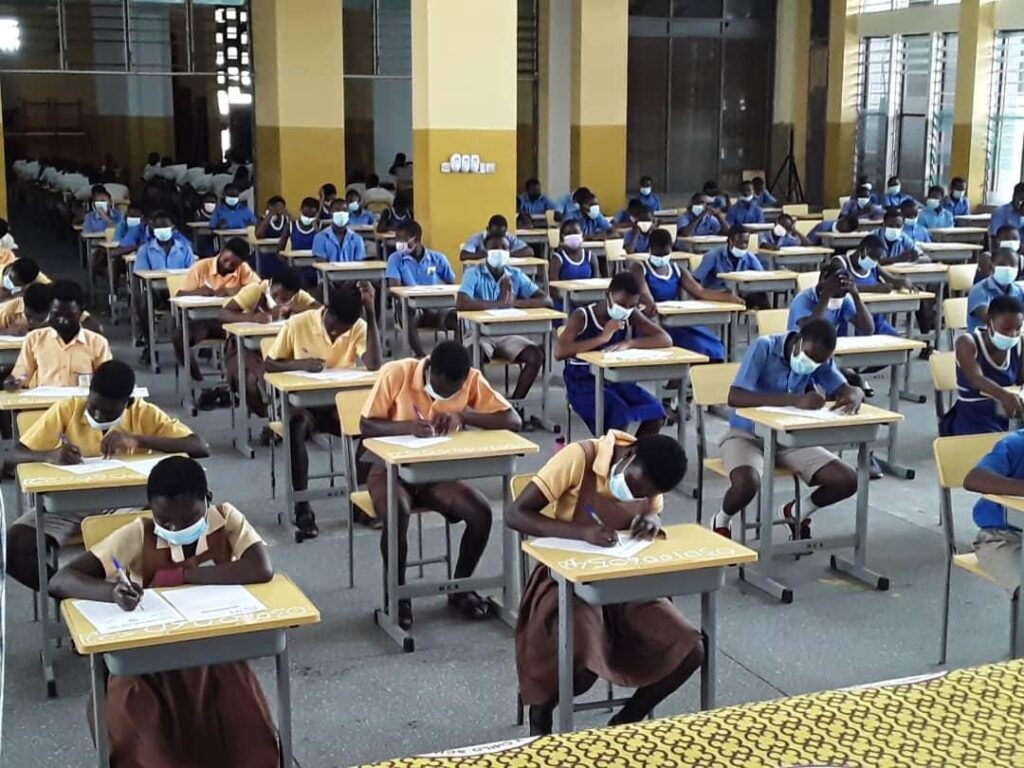

From June 11th to 18th, about 600,000 junior high school Ghanaian students will write the 2025 Basic Education Certificate Examination (BECE).

Every year, thousands of Ghanaian students write this high-stakes exam that determines their placement into senior high school.

Historically, the BECE has long been considered a rite of passage in Ghana’s education system. It’s taken at the end of Junior High School (JHS) 3 and determines which high school a student will be placed in, if at all.

In theory, it’s meant to assess academic readiness for the next stage.

But it might be time to examine whether this exam still serves the best interests of students.

The BECE has outlived its usefulness and should be scrapped in favor of a more holistic, equitable, and modern approach to education.

Instead of focusing solely on exam scores, Ghana’s education system should shift toward competency-based learning, which assesses students on their practical skills, creativity, and understanding of subjects in real-world contexts.

The Problems with the BECE

The BECE encourages memorization rather than actual learning. Rather than fostering creativity, problem-solving, and critical thinking, students are often trained to pass exams rather than to deeply understand concepts.

In a way, Ghana’s high school education has become more like test prep than actual learning, leading to the phenomenon known as “chew and pour“.

The BECE was designed during a time when education was more rigid and linear. Today, we live in an era that values creativity, collaboration, and lifelong learning.

A rigid, summative exam at age 15 doesn’t prepare students for the current, modern, and competitive world.

Better Education Models To Emulate

Originally, the BECE was meant to serve as a filter for students proceeding to senior high school, but with the introduction of Free SHS, nearly all students now transition anyway.

If every student is guaranteed access to secondary education, why maintain an outdated gatekeeping system? Ghana can look at other examples from other jurisdictions to better its education efforts.

Kenya has been experimenting with a new Competency-Based Curriculum (CBC), phasing out the Kenya Certificate of Primary Education (KCPE), which is similar to the BECE.

Their new system emphasizes talent development, soft skills, and formative assessments.

Finland has no nationwide standardized testing until the end of secondary school. Instead, students are continuously assessed by teachers through coursework, projects, and classroom participation.

This approach has produced some of the most literate and well-rounded students globally. It has made Finland one of the best countries for education in the world.

New Zealand uses the National Certificate of Educational Achievement (NCEA), a flexible system that allows students to accumulate credits through both internal and external assessments.

Ghana’s education stakeholders could review these models and adopt something similar for their students.

A Way Forward for Ghana

Ghana’s education system needs reform that reflects modern learning principles.

The country should phase out the BECE and implement continuous assessment through JHS.

The Ministry of Education should help develop a national student portfolio system, where learners build a record of their work and achievements.

They could work with edtech innovators to help develop digital tools for this.

The Ministry could then train teachers to design and evaluate performance-based tasks and project-based learning.

Lastly, placement tests should only be administered where necessary. These tests should be low-stakes and equitable.

If Ghana’s goal is to develop creative thinkers, problem solvers, and compassionate citizens—not just good test-takers—then the BECE is an outdated relic.

Abolishing it won’t be easy, but neither is real reform.

Article was written with the assistance of AI