Within hours of beginning his second term on 20 January 2024, President Donald Trump signed an executive order setting the United States on a path to withdraw from the World Health Organization (WHO) after a one-year period.

The move revived a withdrawal process first announced by the Trump administration in July 2020, which was subsequently halted under President Joe Biden.

So, when the United States formally withdrew from the World Health Organization (WHO) on 22 January 2026, ending a nearly 80-year affiliation as a founding member and its role as the largest single financial contributor to the global health body, the announcement was framed largely as a matter of global politics.

But far from Washington and Geneva, the decision carries a call and consequence globally, with particularly profound implications for Africa, a continent where health systems are still shaped by global cooperation, donor financing, and multilateral coordination.

For decades, the U.S. has been the single largest contributor to the WHO, providing between 15 and 18 percent of its total budget in recent funding cycles.

In the 2024–2025 period alone, U.S. contributions were estimated at close to one billion dollars, much of it directed toward infectious disease control, emergency response, and health systems strengthening in low- and middle-income countries.

The withdrawal represents not just the loss of a member state, but a structural shock to the global health architecture on which many African countries depend.

A Structural Shock to Global Public Health Architecture

In an official statement, the WHO cautioned that the withdrawal “makes both the United States and the world less safe,” and undermines decades of progress against infectious diseases such as polio, HIV, tuberculosis, malaria, and more.

The organization’s Director-General, Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, has characterised the loss of U.S. engagement and funding as one of the most difficult challenges in the WHO’s history, stressing that international cooperation remains essential for addressing shared biological threats.

WHO funding has over the years supported immunisation campaigns, disease surveillance, technical assistance to ministries of health, maternal and child health programmes, and outbreak response.

In many African countries, these initiatives operate alongside national systems that are already under strain, as seen in most sub-Saharan African countries spending less than 5 percent of GDP on health.

Despite the global surge in public healthcare spending amid the pandemic in 2021, on average, African governments spent only 7.4 percent of their national budgets on health care, less than half of the Abuja Declaration target of 15 percent pledged 20 years earlier.

The decision has reverberated across African policy circles.

In Ghana, for example, Dr. Kingsley Agyemang, Member of Parliament for Abuakwa South, warned that the U.S. exit represents a threat to the very architecture of global health coordination on which countries like Ghana depend.

He highlighted that reduced resources could weaken disease surveillance, emergency response, and technical guidance areas critical to managing epidemic-prone diseases such as cholera, meningitis, and emerging zoonoses.

Zimbabwe’s Finance Minister likewise expressed fears that reductions in HIV/AIDS funding post-withdrawal would undermine programmes for people living with HIV, noting that U.S. support through initiatives such as PEPFAR has historically been substantial, often exceeding USD 200 million annually.

Coordination and the Risk of Fragmentation

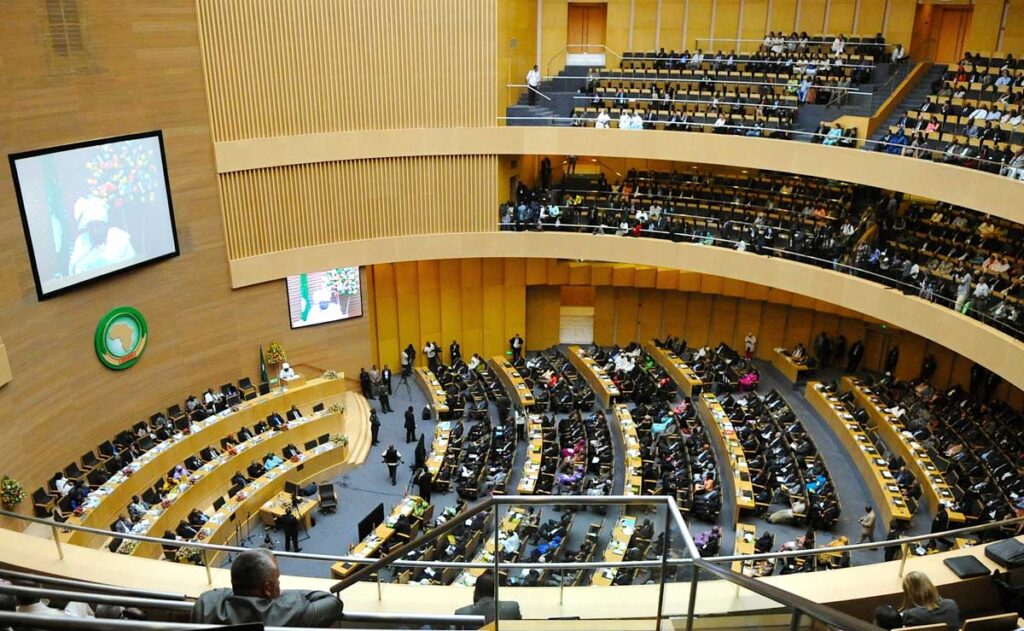

With a health landscape already marked by a multiplicity of actors, bilateral donors, global health initiatives, private foundations, and regional bodies such as the Africa CDC, the WHO has traditionally served as a neutral anchor for collective action.

One of its core mandates has been to act as the central convenor for health standards, guidelines, and donor coordination. In the context of epidemics, this role has meant aligning surveillance systems, streamlining outbreak response, and ensuring equitable access to vaccines and medicines.

When donor leadership weakens, so can the coherence of global responses.

Dr. Agyemang specifically warned that the fragmentation of this leadership risks “duplication of efforts, weaker compliance with International Health Regulations, and partnerships driven more by interests than by public health needs.”

In other words, without coordinated multilateral engagement, countries and funders may pursue parallel programmes that are misaligned, inefficient, and costly.

A Call for Health Sovereignty and Collective Action

In light of these developments, African states face a dual imperative: mitigate the immediate risks posed by reduced WHO support in the future, and build more robust, coordinated regional responses to health challenges.

This coordination will include: strengthening the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC) and the African Union’s health governance frameworks to fill gaps in epidemic intelligence, laboratory networks, and emergency readiness.

Already, Africa CDC collaborates with WHO on outbreak responses and has established platforms for continental disease surveillance and health information sharing.

Simultaneously, African leadership must reinvest in regional and continental cooperation, ensuring that collective responses to pandemics, vaccine distribution, and health workforce development are anchored in shared priorities rather than sectoral competition.

This will go a long way to promote a healthy architecture in which Africa is not merely a recipient of aid, but a co-leader in shaping structures, funding mechanisms, and surveillance networks.

It would be a mistake to view the U.S. withdrawal from the WHO only as a loss. It is also a stress test exposing how vulnerable Africa’s health systems remain to decisions made far beyond the continent.

It underscores the urgency of building resilient, locally anchored systems that are less dependent on political shifts in donor capitals. As the U.S. steps back, other actors are likely to step in.

China has already increased its engagement within the WHO and across African health systems, raising questions about influence, agenda-setting, and long-term alignment.

If global health is, as the WHO’s director-general has insisted, “a shared common good”, then Africa’s response to all this must reflect a strategic vision and a more assertive, unified approach to safeguarding the health of its people.

What happens next will determine whether this moment leads to deeper vulnerability or to a renewed push for equity, accountability, and African-led health systems that are strong enough to withstand global uncertainty.