In a bid to expand financial inclusion while sidestepping religious controversy, the Bank of Ghana (BoG) has introduced draft guidelines for what it terms “Non-Interest Banking” (NIB).

Yet, an analysis of the proposed framework suggests the central bank’s carefully executed rebrand has inadvertently created a confusing, legally precarious “double personality” for the new financial regime, threatening its competitiveness and regulatory stability.

The strategy, intended to avoid the kind of heated religious debate that plagued Nigeria’s introduction of Islamic finance more than a decade ago, attempts to strip the new system of religious language while retaining its theological substance.

One critic argues that this superficial secularization has introduced fundamental contradictions that Ghana’s secular legal and tax systems are unprepared to handle.

The Contradiction: Secular Name, Religious Rules

The core of the issue, as detailed by policy analyst Bright Simons, lies in a profound contradiction.

While the draft guideline prohibits Non-Interest Banking Institutions (NIBIs) from using “any religious connotation, symbol or any other related expression” in their names, it simultaneously mandates that they adhere to the standards set by the Accounting and Auditing Organization for Islamic Financial Institutions (AAOIFI).

“The regulator insists the system is ‘Non-Interest’ (a secular, descriptive, definition) while legally binding it to ‘Islamic’ (a religious, prohibitive, definition) standards,” Simons notes, pointing to a severe market identity crisis.

This clash is more than semantic.

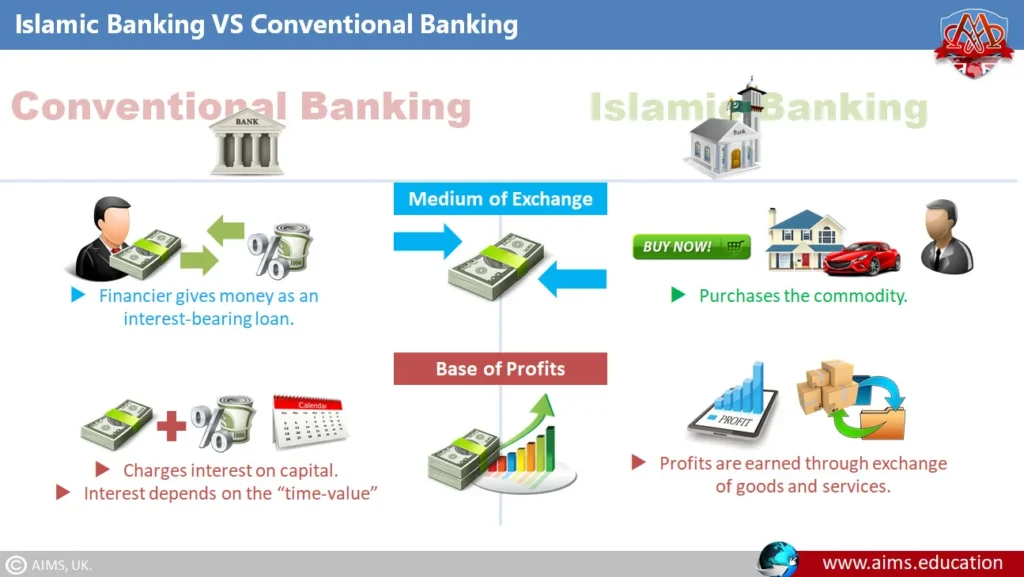

Non-interest banking is rooted in Islamic jurisprudence (Fiqh), which prohibits Riba (usury/interest) and mandates risk-sharing. The BoG’s guideline directly imports classical Arabic legal terms like Mudarabah (profit-sharing partnership), Gharar (excessive uncertainty), and Maysir (gambling) as core definitions, terms which have no foundation in English Common Law or Ghanaian Statutory Law.

This legal ambiguity opens the door for chaos in the country’s commercial courts. Should a dispute arise over a Mudarabah contract, a Ghanaian judge would be forced to either apply the vague, circular definitions in the guideline or effectively resort to religious law (AAOIFI standards) for interpretation.

If judges opt to apply the existing secular Companies Act, they risk voiding the unique risk-sharing provisions that make the contracts Shariah-compliant.

Structural Handicaps and Tax Penalties

Beyond the legal quandaries, the draft guidelines appear to structurally disadvantage NIBIs from a tax and risk management perspective.

The Tax Hurdle: Contracts like Murabahah (cost-plus financing), which is the most common form of Shariah-compliant home or auto financing, are structured as a sale of goods. Under Ghanaian law, a sale attracts Value Added Tax (VAT).

Unlike a conventional loan, which attracts zero VAT, a Murabahah facility would involve the bank buying the asset (VAT paid) and selling it to the customer (VAT paid again), resulting in double-taxation.

Without explicit amendments to the Income Tax Act and Value Added Tax Act—which the draft conspicuously fails to reference—NIB products could be 30 to 40% more expensive than conventional loans, a fatal competitive blow.

The Risk Exposure: The nature of NIB also forces banks into risk-bearing positions that Act 930 (Ghana’s banking law) was not designed to manage. Ijarah (leasing) requires the NIBI to own the leased asset.

This ownership exposes the bank’s balance sheet to significant operational and vicarious liability risks under Ghanaian tort law—for instance, liability in a fatal accident caused by a maintenance failure.

Liquidity Vacuum: Furthermore, NIBIs are expressly prohibited from investing in interest-bearing securities. In Ghana, the safest and most liquid assets are Government of Ghana Treasury Bills and BoG Bills—all of which are interest-bearing.

This regulatory ban structurally bars NIBIs from the country’s primary liquidity management tools, forcing them to hold excessive, zero-return physical cash, thereby significantly depressing their profitability compared to conventional lenders.

A Regulatory Conflict of Interest

The proposed governance structure creates further friction and conflicts of interest. The guideline mandates the creation of two new bodies:

- Non-Interest Banking Advisory Committee (NIBAC): An internal body within each NIBI, responsible for compliance.

- Non-Interest Financial Advisory Council (NIFAC): An external advisory body to the Bank of Ghana.

The NIBAC is tasked with ensuring a bank’s compliance with Shariah principles, yet its remuneration is “determined by the Board of the NIBI.”

This creates a textbook “principal-agent problem,” incentivizing the religious auditors to be “business-friendly” rather than strictly compliant, especially in a competitive market.

Moreover, the draft assigns the NIBAC an internal adjudicatory role in disputed matters.

By having the bank’s own internal committee—the one that approved the product in the first place—act as the judge, the structure appears to violate the principle of natural justice, and risks being struck down by commercial courts.

The cumulative effect of these unaddressed policy issues, critics argue, is that the BoG’s clever rebranding strategy is, as Simons puts it, “too clever by half.”

By attempting to muddle through the “double-personality problem,” the central bank risks launching a parallel financial system that is structurally uncompetitive, legally ambiguous, and prone to regulatory arbitrage.

This article was edited with AI and reviewed by human editors